- Home

- Beth Vrabel

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Page 25

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Read online

Page 25

“So, you guys are done with this poetry thing after this, right? All out of your systems, on to the next hobby?” he said kind of hopefully.

“Poetry is life, Pop,” Jackson said. “Poetry… pop…” He went back to scribbling in his notebook.

Sarah sat next to me, thumbing down her poem with one hand and chewing on her nails with the other. Without thinking, I reached out and squeezed her arm. She flashed me a quick smile. “I’m being silly,” she said. “It’s just a poem, right? And maybe I won’t even perform it.”

I smiled back at her. “No, it’s not silly at all.”

She squeezed my hand. “I knew you’d understand, Pipi. I mean, I really admire you.”

“Me?” I blinked. “Why?”

“I’m scared about how strangers—people I never have to see again if I don’t want to—are going to think of me after I read this poem. But, you? I mean, even after what happened in seventh grade, you just came back to school. And earlier, after the…” Her pretty face twisted and she muffled a gag. “You know.” She motioned throwing up with her hand. “You just kept right on going. I’d look over in the cafeteria and you’d be laughing so hard with Tasha. And I mean, Ricky. He’s been in love with you forever.”

I pulled back my arm. “What are you talking about?”

Sarah bit her lip. “I’m saying this all wrong, I think. I just mean, you’re really brave. My mom calls it grit. She says I don’t have enough of it, that it’s why I shouldn’t stand up to Kara—that I wouldn’t be able to handle the fallout.” Her voice dipped so only I could hear it. “Mom says the only people we can trust are family. Kara says to be quiet and just follow her lead.”

“I know she’s your cousin, but Kara can be really—”

“Awful. I know,” Sarah said. “But it’s just how her family is.”

“Miss Gonzalez says hurt people hurt people,” I said. I thought about Frau Jacobs. “Did… did something happen to Kara? I mean, to hurt her?”

She twisted her fingers, now that the fingernails were gnawed off. She smiled, but it wasn’t a real Sarah smile. More like a smirk. “I used to wonder that, too.” She shook her head. “But it’s like there are two types of people in my family—bulldozers and wallflowers.”

“You’re hardly a wallflower. Everyone knows you. Everyone likes you.”

Sarah’s response was so low I had to lean toward her to hear it. “They know me because Kara makes sure everyone knows us. They like me because I’m nicer than her. Without her? I’d be like… I’d be…”

She didn’t have to finish. I knew what she was too polite to say. She’d be just like me.

“Kara’s like her brother and her mom. They want to be in the middle of everything. If you’re on their side, you can be there, too. If you’re not? Then they’ll knock you over so hard you can’t get back up again. Mom says it’s better to stay on their side. This thing tonight? The open mic? It’s the first thing I’ve ever done without Kara weighing in on it. It’s the first thing that’s just mine. Kara would be furious if she found out.”

I swallowed, the chicken salad sandwich threatening to come back up my throat. I didn’t want to hear this. “Kara’s practically your sister. I mean, she’d get over it, right? And it’s not like you’re doing anything wrong. You’re just doing something without her. She couldn’t be angry with you over that!”

“Have you met Kara? Of course, she’d be angry,” Sarah said. “And any fight I have with her would also be between Aunt Estelle and Mom, too. You know, bulldozer/wallflower. I mean, even when it’s pretty clear that what her kids did was wrong, Aunt Estelle still figures out how to make them the victims. That’s what happened with Max.”

“I remember hearing about how he got suspended—for the locker thing. Where he vandalized a boy’s locker for being gay,” I said. “Eliza told me he was mean to a lot of people.”

“Aunt Estelle tried to justify that. Can you imagine?” Sarah’s face flushed red. “Even knowing…”

“That’s awful,” I whispered back, feeling cold.

Sarah breathed out like she had been underwater.

“Sarah, I have to tell you something,” I blurted. I had to let her know that Kara might show up to the open mic.

“I shouldn’t have told you all of that,” Sarah said at the same time. “It’s family stuff, and I shouldn’t have said it. Family comes first.”

Eliza popped into my head. Sarah’s right, I told myself. Family comes first. And if Sarah really believed that, she’d know that I had to tell Kara she’d be at the open mic night so I could protect my family. “Just remember,” I whispered, “Kara is the one who is wrong here. Not you.”

“Forget everything I said. I’m not making sense,” Sarah continued. “I think I’m just so super nervous and it’s blocking my filter or something.”

“I won’t tell anyone,” I said. Family comes first, I repeated to myself again. But my stomach boiled. “I need to tell you—”

“Thanks.” She breathed out in relief. “I knew I could trust you.”

Just then Mr. Thorpe pulled into a parking spot. All around us, people were streaming into the bookstore for the open mic. I scanned them for Kara. I didn’t see her anywhere.

What if Kara didn’t show up? Then telling Sarah I had given Kara the heads-up about the open mic would solve nothing. It’d just ruin Sarah’s night by making her worried. She probably wouldn’t perform, she definitely would never trust me again, and what good would that do? Except maybe get Eliza fired when Kara found out I double-crossed her, my brain answered.

Honestly, the best thing to do was to stay quiet. If I spotted Kara, then I’d tell Sarah. Honestly, everything was going to be fine.

Chapter Twenty-Six

I had been in the JV Bookstore a few times—it was the kind of place where the workers noticed what kind of book you were reading and brought over a couple others that were just as great. It was in the arts district of the city, one of the old row houses lined up on a road with wide sidewalks and old-fashioned lampposts that were beginning to flicker to life. Inside, the store’s decor was crisp and white with graphic artwork on the walls, dark wood beams across the ceiling, and an all-glass storefront.

That all-glass front was what I was counting on. I’d sit in the back of the room and watch the window. If Kara came toward the doors, I’d spot her and somehow signal to Sarah. But, honestly, I doubted she’d even show. I mean, I told her how important this was to Sarah. I was sure she’d be respectful.

But when we walked in, the shop owners directed us to the back of the bookstore, where there was a narrow staircase leading up to the attic space. Here the walls were faded red brick and the ceiling peaked with wooden planks and crisscrossing beams. There were a couple of windows and a skylight. Strings of yellow lights—the kind usually hanging over outdoor cafes—provided the only light aside from some shaded lamps plugged in at the corners. At the front of the room, there was a spotlight on a wooden stool and a microphone stand. All around it, seating formed a horseshoe. The seating varied; some looked like kitchen chairs, and others were cushioned benches. In one corner, there was an overstuffed, scratched-up leather loveseat.

People wandered around, finding seats. Most of them obviously knew each other from previous open mics—a few even said hello to Sarah or flashed her the thumbs-up. “I can’t believe they remember me,” she whispered. I squeezed her arm. Jackson moved up the small aisle in the middle, choosing a chair two rows back and motioning to us to sit beside him.

“Are you guys sure you don’t want to sit in the back? So we can see everything?” I asked them.

“No, these seats are great!” Sarah chirped.

It’ll be fine, my brain supplied. Just pivot in your seat a little.

Soft music started playing and I looked forward to see a white man, maybe in his mid-twenties, strumming an acoustic guitar. He was wearing jeans and a flannel shirt, his long hair pulled back at the base of his neck. After a few moments

, a black girl moved forward to stand just beside him. She also was in her twenties, I guessed. She wore a magenta, form-fitting silk dress and matching lipstick, her polished look contrasting with the man’s casual appearance. He smiled at her, and she smiled back, nodding softly as he strummed a melody I didn’t recognize. Soon she was humming, and then singing harmony.

After a couple of minutes, he stood and bowed, and she did, too, as people snapped their fingers or clapped. Then they shook hands.

“Do you think they knew each other?” I asked Sarah.

She shook her head. “I told you, this place is magical.”

As the chairs filled, I believed her. I had never seen so many different and diverse people in one space.

An old woman with long, gray hair and a flowing dress sat down behind us. Next to her was a younger woman who looked like any of the moms in the school pickup line at the end of the day, wearing what my mom called a “statement” necklace, a turtleneck, and slacks. A group of older teenagers showed up, and then a cluster of college-aged kids joined. An Indian couple took the bench in front of us, holding hands and whispering jokes into each other’s ears. We were among the youngest, although the beautiful woman standing by the door greeting people had a small son with a mop of dark hair with her; he sat at her feet reading a book that seemed too thick for someone his size, while his mother’s laughter filled the room. At the front of the room, another woman with long, wavy hair and a smile that made me smile back even though it wasn’t directed to me set up a podium next to the stool. She hugged a blond teenager in a cheerleading uniform, who took a seat on the stool and began singing a solo of a popular song, somehow making it dreamy instead.

After a few minutes, the woman who had been greeting people at the door moved to stand in front of the microphone. “Welcome to the JV Open Mic!” She introduced herself as a poet and professor at the local university, then laid out some rules for the event. Each speaker would have no more than ten minutes to perform and each audience member would allow that person to be heard. “Today we’ve had a request to skip the live stream and keep things a bit more intimate, so know that if you speak your truth, it stays in this room.” Then she welcomed the other woman—the one with long hair and a wide smile—to the floor. The woman moved the stool to the side and stood, her back arched with a confidence that reminded me of Piper. She warmed us all with her smile.

I kind of understood what spoken word poetry was from Sarah and the videos she had shared with me, but being there, listening to this poet, was so different. The words seemed at times to begin at her toes, sprouting through her to blossom in front of us. She spoke about the power of names, the ones we are given and the ones we assume. I couldn’t look away for a moment as she spoke about becoming herself, fully and truly, and when she talked about the sadness that colored her joy, I ached, feeling it in a way that words alone never had been able to do.

“Wow,” I whispered to Sarah. “Is everyone like that?”

She smiled and shook her head. “No one is like that. But I think we all try to be.”

A girl only a couple years older than us went next. Small and pale, she used a white cane as she strode purposefully forward and then lowered the microphone. The font on her printed pages was large and dark enough for me to see a couple rows back as she organized them on the podium. “I’m going to tell you about the time my family surprised us with a vacation,” she said with a wide smile that quickly faded—although everyone else laughed—as she added, “to Cleveland. In the winter.” Her poetry shifted from stand-up comedienne funny to achingly poignant and then back to humor.

“Wow,” I whispered again to Sarah, who mouthed, “Right?”

Next a middle-aged white man took a seat on the stool. He held a lined piece of notebook paper in his hands and read in a soft, lilting voice a story about a dragon climbing up a mountain from a cave. The paper in his hands shook just a little, enough to show me his bravery. The applause when he finished was just as strong.

A tall black man wearing a hoodie from the local university smiled over his shoulder at the hostess as he walked up the aisle to perch on the edge of the stool. “I wrote this on the way here,” he said, and then softly began a poem that quickly gathered steam until my heart pulsed with his words.

On and on people took the stage, being beckoned by the woman who had greeted most of the people at the door. She was as young or younger than most of the audience, but somehow felt like the mom, if that made any sense. Maybe it was the way she threw open her arms to welcome every speaker.

Jackson went next, with Sarah and I clapping so hard that my palms were red as he took the stage.

“Uh, I just started writing poetry,” he said. The spotlight added a halo around his head and he grinned, flashing his dimple. I waited for the usual rush of heart fluttering that always hit me when Jackson smiled. Instead, I just felt happy—happy for my friend. Guess we’re not crushing on Jackson anymore, my brain pondered. And then, in a totally uncalled-for move, it flashed a picture of Ricky in my mind. Not fair, Brain. Not fair.

Jackson gave his “sitting on a sphere of air” poem, which actually did sound a lot more philosophical when he wasn’t literally sitting on a ball of air. When his ten minutes were up, the hostess walked to the stage while clapping. She beamed at him and told him she was so proud and so excited to see how he would continue to develop his ideas. Jackson grinned and bowed.

“Next up,” she said after a few performers, some of whom took up the full ten minutes and some who only spoke for a minute, “is Harp, who’s here with their partner Lila. Sometime soon Harp and I will convince Lila to share her story, but for now, join me in celebrating Harp!”

One half of the couple in front of us went up to the stage.

Harp smiled into the audience like a kid in front of birthday cake. They spoke about family and how it meant love and nothing else. All around me, people snapped instead of clapping so as not to interrupt their performance. While they spoke about falling in love, tears streamed down Lila’s smiling face. A lump formed in my throat as I thought about my family and how lucky I was that love was just a given.

“Anyone else?” the woman asked when applause for Harp dampened. I glanced around, saw no one new, and nudged Sarah, who nodded and stood. Her face glowed. She glowed. Sarah had always, always been the pretty girl in our grade, but seeing her glide toward the front of the room, she seemed different. This place is magic, she had said when we arrived. She was right, and she was transformed. She wasn’t pretty; she was powerful.

I bit my lip watching her take her seat on the stool. She held her phone in her hand but barely glanced at it. “So, this is the first time I’ve done this,” she said. Most of the people snapped and her smile stretched. “But I feel like I’ve been writing this poem forever. Which I know, being that I’m thirteen, doesn’t sound like a long time.” Laughter trickled through the room. “I’m also super grateful for the spotlight because I can’t see any of you right now.” Now the laughter was even stronger.

“So, here’s my poem. It’s titled ‘Confusion.’” She cleared her throat. After a big breath, she recited,

When I told them, they said,

“Oh, you’re just confused.

You just need time.”

But I’ve been listening to the clock,

I’ve watched its hands

sweep across its blank face only to repeat itself and

I am not confused.

Maybe others will say I don’t know,

That I’m too young to know my heart

or to understand how this works,

But I live in this body.

I feel this heart pump

And each pulse tells me that

I am not confused.

Sarah paused. A tear glinted on her cheek, even though her face still glowed. In front of me, Lila and Harp snapped, joining a chorus all around us. I glanced at Jackson and he was smiling so big, nodding with each word that Sarah spoke. I

felt the same smile on my face. I realized I had always seen her as one half of the Sarah-Kara whole. But on her own, she didn’t seem tiny and fragile. On her own, up there on the stage, she was powerful. She was strong. I wanted that bravery for myself. Sarah wasn’t as polished or as powerful as the first speaker—yet. But she looked so at home, speaking her truth. She smiled and finished the poem.

I will make my words simple.

I will make them direct.

I will make them clear.

I will say that I know what I know

And I know that love is what matters.

This body, this heart, this girl

standing in front of you?

That is what matters.

And she’s telling you her truth.

How could that ever

Be confusing?

For a moment no one spoke or moved. Sarah cleared her throat again, took another deep breath, and smiled out to us. I jumped to my feet, clapping so hard and smiling so much I thought both my face and hands would crack. I wished I could do one of those awesome whistles with two fingers, but luckily Jackson could, and did.

“So, yeah,” Sarah said as audience members slowly settled back into their seats. “I’ve been here before and I just listened. And I caught a couple live streams, too. Really glad there wasn’t one tonight,” she said to more laughter. “My two best friends—they’re here with me—know I’m gay.” Something in my chest twisted, a knife slipping between my ribs, at Sarah calling me her best friend. If she knew you risked this moment for her…

Sarah continued, “My family knows, too, but ignores it. But I’m tired of ignoring who I am.” Snaps broke out around the room. Sarah nodded. “I thought if I could be brave here in front of all of you, I could carry that with me, wherever I go.” More snaps. She took a deep breath. “Next year, I’ll be in high school, and we have to do a service project. I’m going to make a gay services alliance club.” Sarah’s chin lifted. “Maybe I’ll be the only member, but I won’t be alone.”

The Newspaper Club

The Newspaper Club The Humiliations of Pipi McGee

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Camp Dork

Camp Dork Pack of Dorks

Pack of Dorks Bringing Me Back

Bringing Me Back The Reckless Club

The Reckless Club A Blind Guide to Stinkville

A Blind Guide to Stinkville A Blind Guide to Normal

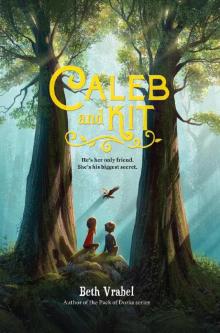

A Blind Guide to Normal Caleb and Kit

Caleb and Kit