- Home

- Beth Vrabel

A Blind Guide to Normal

A Blind Guide to Normal Read online

Praise for Beth Vrabel’s Pack of Dorks and A Blind Guide to Stinkville

“Debut author Vrabel takes three knotty, seemingly disparate problems—bullying, the plight of wolves, and coping with disability—and with tact and grace knits them into an engrossing whole of despair and redemption…. Useful tips for dealing with bullying are neatly incorporated into the tale but with a refreshing lack of didacticism. Lucy’s perfectly feisty narration, emotionally resonant situations, and the importance of the topic all elevate this effort well above the pack.”

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Lucy’s growth and smart, funny observations entertain and empower in Vrabel’s debut, a story about the benefits of embracing one’s true self and treating others with respect.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Vrabel displays a canny understanding of middle-school vulnerability.”

—Booklist

“Lucy’s confident first-person narration keeps pages turning as she transitions from totally popular to complete dorkdom in the space of one quick kiss…. Humorous and honest.”

—VOYA

“This book doesn’t soft-pedal the strange cruelty that kids inflict on one another, nor does it underestimate the impact. At the same time, it does not wallow unnecessarily…. The challenging subject matter is handled in a gentle, age-appropriate way with humor and genuine affection.”

—School Library Journal

“Pack of Dorks nails the pitfalls of popularity and celebrates the quirks in all of us! An empowering tale of true friendships, family ties, and social challenges, you won’t want to stop reading about Lucy and her pack … a heartwarming story to which everyone can relate.”

—Elizabeth Atkinson, author of I, Emma Freke

“A book about all kinds of differences, with all kinds of heart.”

—Kristen Chandler, author of Wolves, Boys, and Other Things That Might Kill Me and Girls Don’t Fly

“Beth Vrabel’s stellar writing captivates readers from the start as she weaves a powerful story of friendship and hardship. Vrabel’s debut novel speaks to those struggling for acceptance and inspires them to look within themselves for the strength and courage to battle real-life issues.”

—Buffy Andrews, author of The Lion Awakens and Freaky Frank

“Beth Vrabel weaves an authentic, emotional journey that makes her a standout among debut authors.”

—Kerry O’Malley Cerra, author of Just a Drop of Water

“Most commendable is Vrabel’s focus on compromise and culture shock. Disorientation encompasses not only place and attitude but also the rarely explored ambivalence of being disabled on a spectrum. Alice’s insistence that she’s ‘not that blind’ rings true with both stubbornness and confusion as she avails herself of some tools while not needing others, in contrast to typically unambiguous portrayals. Readers who worry about fitting in—wherever that may be—will relate to Alice’s journey toward compromise and independence.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Brimming with wit and heart, A Blind Guide to Stinkville examines the myriad ways we define difference between ourselves and others and asks us to reexamine how we see belonging.”

—Tara Sullivan, award-winning author of Golden Boy

“A Blind Guide to Stinkville is a delightfully unexpected story with humor and heart. Vrabel tackles some tough issues, including albinism, depression, and loneliness, with a compassionate perspective and a charming voice.”

—Amanda Flower, author of the Agatha Award–nominated Andi Boggs series

Also by Beth Vrabel

Pack of Dorks

A Blind Guide to Stinkville

Camp Dork

Copyright © 2016 by Beth Vrabel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously.

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Laura Klynstra

Cover illustration by Chris Piascik

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0228-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0229-5

Printed in the United States of America

To Goldie, my papaw’s long-passed devil cat, for inspiring the General. It almost makes up for the lifelong fear of exposed ankles while walking down stairs.

Chapter One

Even I could see that the cake was one twisted joke.

As my friend Alice pushed a cart to the front of the classroom, everyone else backed off, distancing themselves. And since this was a room full of kids attending Addison School for the Blind, it also clued me in that they all had seen the cake before Alice wheeled it in.

Brad (all of our teachers at Addison insisted on being called by their first names) moved the projector so it blew up an image of the cake onto the wall. He read aloud the words set in red icing: “Good luck, Ryder! I’ll miss you.”

Alice broke in, “But it’s really ‘Eye’ll miss you.’ E-y-e!” She snorted at her own joke.

Quiet fell across the room like a blanket.

“Eye,” Alice added in a whisper, her usually white-as-paper cheeks pinking as the silence thickened. She stepped closer to me. When I knew she could see, I slowly shook my head, like I was so disappointed. “Um,” she continued, face flaming, “sort of like how you only have one eye …”

“That’s just sick.”

Alice squirmed and I couldn’t hold it in another second, laughter ripping out of me. The worst torture in the world is forcing some poor fool to explain a joke. I took off my glasses and pretended to wipe the lens with one hand. After a second, I popped out my fake eye with my other hand. “If you’re going to miss it, Porcelain, I could just leave it behind.”

Alice slapped away my hand. But she couldn’t stay mad at me. No one can. It’s a gift. Soon she was laughing even harder than I, making everyone join in. No one can resist Alice’s laughter. I guess that’s sort of her gift.

“He’s holding his eye, isn’t he?” asked Lucas, who had started at Addison School in sixth grade like me. But where I was about to head back to public school for eighth grade—hence the going-away party—Lucas would probably graduate from Addison. I, at least, have mild to low vision out of one eye. Lucas was born totally blind.

“Yup, he sure is,” Alice said. Although she is technically blind due to albinism, Alice usually just had to get close to something to make out what was going on around her. I smiled, a little pumped that she and Lucas had each other. Thanks to me. I kind of took Alice under my wing when she arrived at Addison a year ago. At first, I just liked making her blush—calling her Porcelain because of her pale skin and stuff like that—but we quickly became friends. Best friends, actually.

Alice and Lucas, however … well, Lucas slipped his hand into hers like he could hear my thoughts.

“Speech! Speech!” chirped Lucas, raising their

joined hands in a little rally punch.

Alice picked up the chant. “Speech! Speech!”

“All right!” I groaned, but, you know, eating up the attention anyway. I cleared my throat. “My dear people! I don’t know half of you half as well as I should like; and I like less than half of you half as well—”

“Hey!” Brad interrupted. “That’s Bilbo’s farewell speech!”

“Told you I was paying attention in reading class, Teach.”

“Too bad you couldn’t recall lines like that during the exam,” he volleyed back.

“Wow, Brad. Just when you’re getting good at these witty comebacks, I’m off. I expect the rest of you to keep him on his toes.” I cleared my throat again. Suddenly, looking around at my friends, I couldn’t swallow right. “Seriously, though. Thanks for this, guys. Try to hold it together without me. Someone will need to keep an eye out for the newbies.”

“But not literally!” added Alice, slicing into the cake. “Shall I save the pupil for you?”

“Absolutely.” I grinned like a fool and passed out slices of my giant farewell eyeball cake.

“Going to miss me, Porcelain?” I asked Alice later. We were waiting by the curb in front of the main building for her mom to pick her up. Where most of the kids—like me—boarded at Addison, Alice lived less than an hour away, so she went home each afternoon. Usually we joked around and rehashed our day while waiting for Alice’s mom, but knowing it was the last day of school—and my last day at Addison—made it feel sort of awkward.

All around us people were lugging bags to the sidewalk. Parents were pulling up with their hazard lights on, honking horns, and calling out names. I guess it was like any last-day-of-school pickup, except for the clicking of canes against the sidewalk. Alice folded up hers and rested it across her knees as we sank down to sit and wait.

“Of course, I’ll miss you,” she said. “But you’re going to text me every day, right?”

“Right.” I beamed a huge grin across my face.

“You know if you don’t stop smiling like that a fly’s going to land on your tongue.”

“I can’t help it,” I said. “I’m just so … I don’t know. I can’t wait for next year, to get back to normal. Be surrounded by normal—” I bit off the stupid thing I was going to say but it was too late. Alice’s face flushed again but not from embarrassment. Man, I can be such a jerk sometimes. “Alice, I didn’t mean it like that …”

She sighed. “I know. Being here, it makes me forget sometimes. Makes me think I’m normal.”

“You are normal! You’re totally normal! You’re like the most normal, run-of-the-mill person—”

“That hole you’re digging is getting deeper.” Alice laughed. “Besides, I don’t think normal exists.”

“I shouldn’t have used the word normal,” I said quietly. “I just meant regular. I’m excited to go to a regular school.”

“You don’t think it’s going to be hard?”

I shrugged. “A little, I guess.”

Alice nodded. “You know, it’s strange. A year ago, I was so mad that my parents were making me check out this place. I was sure I didn’t need it. Now, I get the same nervous feeling when I even think about going back to Sinkville Public. And that’s the school in my town! Where I know everybody! Here you are, moving to a new town and not scared at all.”

“Well, when you put it that way, my palms get a little sweaty.” I knocked into her shoulder with mine so she’d know I was joking.

I guess most people would be nervous in my situation. My parents are research biologists. Mom specializes in entomology (you know, bugs) and Dad in wildlife (anything with vertebrae, but he loves buffalo the most). They travel all over America for assignments that can last anywhere from three months to a year or more. Since I’ve been at Addison, I usually join them wherever they are for the summers. It can get a little lonely, like when we were tenting it in Idaho. Spring Break was pretty awesome, though. Mom nailed a spot in Hawaii. I came back with a killer tan, even though Alice pelted me with stats about skin cancer.

The whole albinism thing keeps her perpetually smelling like coconuts from all the sunscreen she coats on. Even now, though it was a cloudy afternoon, she wore a wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses, and I still sniffed that faint coconut odor.

“It’s Dad’s turn for an assignment this summer,” I said. “So I’ll be four-wheeling across three-point-six million acres of public land in the middle of Nowhere, Wyoming. But Mom says she’s a shoo-in for an office research spot in Washington, DC, after this gig, so I can go to a real school in the fall.”

“That’s great,” Alice said, but I could tell she didn’t mean it, really.

“Worried you’re going to miss me?”

“A little, I guess.” She smiled as she copied my words. “I just hope everyone at your ‘normal’ school can see what a great person you are.”

“Why wouldn’t they?” I threw out my hands in a what’s-not-to-love sort of way. I elbowed her as her mom’s car pulled up in front of us.

“You’re going to be fine,” she said, but I think she was trying to convince herself more than me. Alice isn’t always the most confident of girls.

Mrs. Confrey waved from behind the front seat. She looked like a taller, more elegant Alice, only with a curtain of black hair instead of Alice’s white locks. “Hey, Ryder! Alice, hurry up! We’re meeting your dad for milkshakes.”

Alice almost knocked me over, throwing her arms around me in a huge hug. “Bye, Ryder,” she whispered, her voice catching.

“Hey, doll, knock it off. I’m going to text you. And I’m sure you and Lucas will meet loads of new friends next year.”

“Yeah, but none of them will be as easy to find in a crowd,” she said, ruffling up my hair with her hand. Alice confessed a couple months ago that when she started going to Addison the only reason she kept talking to me was that, thanks to my bright red hair, I was the only person she recognized in the hallways. She got up and started to walk away then doubled back. “Ryder?”

“Yeah?” I asked, turning my head to see her better.

“Don’t call the girls ‘doll’ at your new school, okay?” She said it in a rush.

I leaned back on my elbows, squinting up at her. “Are you jealous or something?”

Alice puffed out of her nose like a bull. She crossed her narrow white arms. “No, dimwit. It’s just not something I think you’re going to be able to get away with at your normal school.”

I grinned. “I am who I am, doll. This cheetah isn’t going to change his spots.”

Alice nibbled on her bottom lip until her mom honked the horn again. “Most guys don’t say things like that, too, about cheetahs and spots.”

I shrugged. Whatever, you know? I was unique. And, all right, maybe spending most of my life cracking up my folks instead of other kids made me more of a wordsmith than most guys my age. They’d catch up.

Alice waved until she couldn’t see me anymore as her mom drove away. On the way back to my dorm, where I still had to pack, a couple dozen people stopped me for fist-bumps, wished me luck, and promised to stay in touch.

It should’ve hit me then—being celebrated like a departing rock star. I should’ve realized.

Because here’s a joke for you (only it’s really a joke on me): Where can a cocky, one-eyed ginger be the coolest cat around?

Punchline: Only at a school for the blind.

Chapter Two

Here’s another joke. Not one of my finest, but it’ll do: What did my dad say at the end of a summer of watching elk herds in Wyoming, as he dropped me off at his father’s so he could research buffalo in Alaska?

Bison.

Get it? Bye, son. I know. Bad joke. Even worse when it reflects real life.

“I know it’s not ideal, Ryder,” Mom murmured from the front seat as she shifted the car to park in front of Gramps’s house.

“I don’t even know him.” I could hear the whine in my voice but Mom

didn’t squash it like she normally does. She let out a long breath through her nose instead. I read somewhere that if people spend too much time with their pets, they start to look like each other. I think it’s got to be true for researchers and their subjects, too. Mom has huge eyes, a round face, and a tiny thin-lipped smile, plus vibrant red hair always pulled into a tight bun on top of her head. In other words, she’s like a mom-sized ladybug.

Next to her, Dad grumbled. He had tight brown curls covering his head with a bushy mustache topping his lip. More hair curled out under the neckline of his chest. He was wide as two average-sized dads and could hike for sixteen hours straight without a break—or the understanding that others (such as, I don’t know, his kid) might need one.

“You and your mom will get along just fine with your grandfather,” Dad boomed. “You remind me a lot of him.”

I tried not to take that personally. After all, Dad left home for college when he was seventeen and never came back. He calls his dad once in a while, but it wasn’t not like we saw each other at holidays or anything.

In fact, I hadn’t seen Gramps since I was seven, right after the surgery I had to remove my eye. He stayed up all night in the hospital bed next to me, telling terrible knock-knock jokes and watching awful television shows until I laughed. Then he patted my head and left.

“It’s very gracious of him to take us in,” Mom said.

I don’t know how to describe the noise that pushed out of my lungs, but it got my point across. Mom squeezed shut her eyes and rubbed at them with the heel of her hand. “You know this is a great opportunity for your dad. A time when his research really could make a difference! And steering this project in DC is going to mean a lot of late nights for me. Moving in with your grandfather is the best solution for all of us.”

Here was the deal: That summer-long research project in Wyoming was supposed to be followed-up with a laboratory research job for Mom in the DC area, right? Everything was going on track. Heck, I even got to man a four-wheeler one memorable occasion. (Imagine driving with your foot pressed solid against the gas while a crazy elk charges you over roots and rocks. Now close one eye.)

The Newspaper Club

The Newspaper Club The Humiliations of Pipi McGee

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Camp Dork

Camp Dork Pack of Dorks

Pack of Dorks Bringing Me Back

Bringing Me Back The Reckless Club

The Reckless Club A Blind Guide to Stinkville

A Blind Guide to Stinkville A Blind Guide to Normal

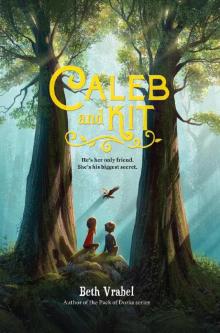

A Blind Guide to Normal Caleb and Kit

Caleb and Kit