- Home

- Beth Vrabel

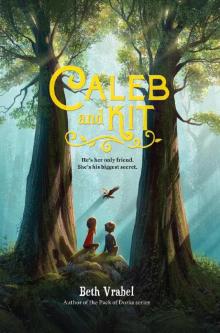

Caleb and Kit

Caleb and Kit Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2017 by Beth Vrabel

Illustrations copyright © 2017 Erwin Madrid

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Running Press Kids

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com/rpkids

@Running_Press

First Edition: September 2017

Published by Running Press Kids, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016953715

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6223-0 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-6224-7 (ebook)

E3-20170810-JV-NF

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Acknowledgments

Praise for Caleb and Kit

WILL, JACK, AND JOEY

CHAPTER ONE

Kit said we were destined to meet, but I really was just going for a walk.

I had to get out of the house and away from my brother, who was sawing on his violin so hard that the noise seemed to vibrate up through my chest and out of my ears. Maybe he was just practicing, but then again, maybe my perfect brother was showcasing yet another way he was better than me. Back went the bow. Look at what I’m doing while you just sit there! Forward. When I was twelve, I’d already performed concertos. Back. I’m captain of the cross-country team, but you can’t even run a mile. Forward, entering the cadenza. Pathetic! Back. Loser! Forward. Lazy!

Not that Patrick would actually say any of those things. He was too polite, too considerate, too perfect for that.

I had to leave. I grabbed my backpack and shouted over my shoulder, “Going for a walk!”

I thought Patrick wouldn’t be able to hear me, but I suppose I had to add super-hearing to my big brother’s long, long, long list of skills.

“Some exercise is a good idea, Caleb!” he hollered, now easing back into the concerto’s slow ending. “Don’t overdo it. Bring your—”

The door slammed behind me before he could finish. Patrick always acted like he was my parent just because he’s five years older than me. The music stopped before I got to the end of the driveway, and the door flew open again with a bang.

Patrick stood there with his violin in hand. “Wait! Caleb, I’ll go—”

Before Patrick could finish his offer to come along, I quickened my pace and ducked from the driveway, even though that meant plunging right into the woods that border our house. I knew Patrick would put away his violin carefully and exactly before following me, but that only gave me a couple seconds’ head start, so I had to act fast. I jumped over a fallen log. Briars scraped the sliver of skin between my socks and my pant leg, but I plunged ahead anyway.

I hardly ever went into the woods surrounding our house. Brad, my best friend, usually came by on his bike, and we’d stick to the cul-de-sac, playing pickup when I felt up to it, H.O.R.S.E. when I didn’t. We used to race in electric go-karts. Mom still kept them charging in the garage, just in case Brad decided they weren’t too babyish anymore now that we were twelve. Part of me thought he said they were babyish because I was so much better at drifting than he was, and he didn’t know how to handle being slower than me.

But Brad wasn’t around much now that he had both baseball and football practices.

Once the woods were thick around me, I figured Patrick would have given up on finding me and retreated back into the house. I looked up to the branches of the huge trees above me. Two long, thick trunks soared straight to the sky and then curved away from each other. I had heard once about trees that do that—live side by side but bend away to share the sun. They are buddies. They could stick close, but if they do, eventually one will struggle to tower over the other, keeping the weaker, unluckier one in the shade. Instead, if they are really friends, they’ll bend apart. I wondered if it hurt, twisting away from your friend like that.

I squinted, and for a second the branches looked like the inside of a pair of lungs, stretching in all directions from the trunk, always reaching for more, more, more.

My own lungs ballooned as a breeze rustled through the trees’ leaves. Hoping I wouldn’t get lost, I went deeper into the thicket. Here’s the thing: I live in a small neighborhood. It wasn’t like these woods would stretch for miles. A couple acres, maybe, tops. Other people’s houses bordered the thick circle of trees like mine, so the worst that could happen was that I’d end up across the woods in someone’s backyard.

That was what I told myself anyway. I yanked the backpack strap up my shoulder and unzipped the front compartment, making sure my inhaler was there. It wouldn’t buy me a lot of time, but it was better than nothing.

I decided the best direction to head was straight back. If I stayed on the path I’d forged, then all I’d have to do to find my way home was turn around, right? Yeah, I guess that’s why I’d never make it as a Boy Scout. Of course as soon as I couldn’t see my house anymore, that’s when the trees got all squished together like bullies, totally zapping the chance of my walking in a straight line. I stepped over broken branches, around trunks, through prickly bushes. There was no way I’d find my way back now by just turning around.

Each step I took made my shoes suck deeper into mud with a squelching sound, and each time I lifted my feet it made my chest hurt. A few more yards in and I realized I was in trouble. My chest burned. I tried to ignore it. The pain twisted and coiled around my ribs—not like I couldn’t breathe but like my body didn’t want to. Like I was drowning from the inside out. I tried not to think about how fast my heart was beating and only that totally freaking out was useless. I tried not to croak out a cry or anything babyish like that. This wasn’t my first panic attack; I knew I wasn’t really dying. But every time it happened, I had to convince myself all over again. And the attacks had been happening more and more.

I tried to focus on what was going on around me. Sunlight trickled through the thick woods. Maybe there was a clearing? The opening was also the reason for the gross mud I was plodding through. Just inside the clearing there was a stream that cut through the woods. The stream was shallow, only a couple inches deep, but wide, stretching as far as my yard. Sunshine glinted off the water, where it trickled over stones the size of my fist and around large boulders.

I’m not dying, I told myself over and over. I’m not dying. It was just a panic attack.

I’m okay. I fell to my knees, not caring when they sank into the mud, drenching

my pant legs with thick dark muck. Leaning forward, I plunged my palms into the cool water. I’m okay. The smooth, cold rocks seemed to be pressing back as much as my hands pushed against them. I’m okay.

The slow lap of water over my skin helped me focus. I concentrated on what Mom had told me to do when I got like this—count out my breaths, make sure the exhales matched the inhales, try to make each last a count of three, then four, then five. Five is fine, she always said. When you get to five, you know you’re okay. What she meant was: if I could stretch out each breath to five seconds, then it was just my head that was convinced I was dying. Not my lungs. Still, I thought about my inhaler, zipped in the front pocket of my backpack. Was it time to grab it?

I held off, breathing in and out instead, counting. Like usual, Mom was right. I flexed my fingers in the water, noticing for the first time the minnows racing around the stones and the sudden flush of swirling mud when a crawfish hid beneath a loose rock.

Even though I felt better (relief over not actually dying sort of washed away the whole lost-in-the-woods worry for the moment), I stayed put, searching for the bluish-gray crawfish in the settling water. It only took a few seconds for me to spot it creeping along, its oversize pinchers outstretched. Quick as I could, I plunged my fingers into the stream to catch it. Its tail sent a swish of water between my fingers as it dashed away.

“You’ve got to be a lot faster than that.”

The voice above made me jerk, sending my already drenched knees slipping into the water. This time the voice laughed—a tinkling sound.

I rose to my feet, face burning, and squinted into the sunlit clearing to see who was talking. A huge boulder sat in the middle of the stream. And on top of it, her legs folded neatly beside her, perched an angel.

Stupid thought, right? But I swear, the sun shone straight on her, making the top of her dark brown hair glimmer like a halo and the yellowish boulder upon which she sat shine like gold. Oh, man. Had I been wrong? Maybe it hadn’t been a panic attack. Maybe I had died!

The girl laughed again and slid down to land barefoot in the water with a quick splash. She walked toward me with a wide smile and her hands folded behind her back. “I’ve gotten really good at catching them,” she said. “You’ve got to put one hand behind them, and then, with your other hand, splash the water in front of them. They’ll fly right back into your first hand.”

“Oh,” I mumbled, my face flaming. “How—how long have you been here?”

The girl’s bottom lip jutted out for a moment and she looked up toward the sun as if doing math in her head. Her eyes were pale blue like a patch of sky behind puffy clouds. Freckles sprinkled across her nose and cheeks. “Maybe an hour or so,” she said. “I’m trying to catch a bird, but they all keep ignoring me, even when I whistle at them.”

“A bird? Why?”

“Well,” the girl said as she smoothed her hands on her ratty white sundress, “I’ve figured out how to catch the crawfish and the minnows. Seems like birds would be next.”

The corner of my mouth jerked upward. “Quit messing around.” But even as I said it a dark crow swooped overhead.

The girl shrugged her narrow shoulders, and I knew she hadn’t been joking.

“You really want to catch a bird?”

The girl nodded.

“Why?”

“Why not?” She smiled again. I guess I was still making sure she was real, because my brain seemed to pick up on things about her that I don’t usually notice with other people. Things like how her chin was small but pointed, how one of her front teeth slanted over the other, how her eyelashes captured sunlight as much as her hair. It made remembering to talk take longer than it should have.

“Because…,” I managed because I was apparently an amazing conversationalist.

“Because…,” she repeated.

“Because… what would you do with it once you had it?”

The girl’s smile stretched wider. “I haven’t thought that far ahead yet.” She jerked out her hand to shake like we were parents meeting in the school parking lot instead of two kids standing in a stream. “I’m Kit. I live here.”

“Here? In the water?”

She laughed again, but not in a mean way. “Of course not, silly. I live in a house that way.” She jerked her thumb over her shoulder toward the other side of the stream. “And you?”

“Oh.” I smoothed my wet palm against a dry part of my pants and shook her hand. It was warm, probably from the sun-drenched rock she had been sitting on. “I’m Caleb. I live that way.” I nodded my head backward. “At least I think I do. I’m sort of lost.”

“Awesome,” Kit said. You know how people talk about eyes sparkling? I always thought that was just a stupid thing people said when they meant someone looked happy. But it’s not, because Kit’s eyes could do that. They sparkled. If she were a comic book character, a little ding would be written in curly letters over her eyes. “Getting lost means you get to have an adventure.” She stepped backward into the stream, her eyes steady on mine like a dare. “Are you ready?”

I didn’t normally do this kind of thing—follow random girls deep into the woods, I mean. But I didn’t even have to think this time. I just kicked off my sneakers and tossed them onto the bank. “Ready.” I followed her across the stream.

Kit led me along a narrow trail deeper into the woods. She stopped suddenly, and I bumped into her. “Look!” She pointed to long, skinny blossoms hanging from weeds growing along the path. The flowers looked like tiny trumpets. “Honeysuckles!” She plucked a blossom and peeled back the petals. Then she popped the middle into her mouth.

“Try one.” She handed me a blossom. Her fingernails were brown, probably from catching so many crawfish in the mud.

“Are you sure you know what these are?”

Kit didn’t answer, just peeled another flower. I sniffed at the blossom. It smelled like honey but, when I put the edge on my tongue, it tasted more like perfume.

“How old are you, anyway?” Kit asked, an eyebrow raised as she studied my face.

I lifted my chin, threw my chest out. “I’m twelve.”

That eyebrow popped up a smidge higher. I knew why. I didn’t look like a twelve-year-old. I was sort of like Chris Evans at the beginning of the first Captain America movie—the part before the scientist gave Steve Rogers the elixir of super serum and he was just frail looking and scrawny. I’m too short and way too skinny for my age. I’m so used to the air fighting its way out of me that sometimes I forget to close my mouth when I breathe; Patrick says it makes me look like a toddler with my stomach puffed out and mouth hanging open. My brown hair is long, I guess, and it flops on my head instead of lying flat and smooth like Brad’s or waving back over my head like Captain America’s. Also not helping me in the looking-my-age department are my huge brown eyes; they’re the reason Patrick used to call me Bambi—that is, until Mom grounded him from playing his violin for a weekend when I made a huge fuss about it.

I braced myself for Kit to do what everyone else did when they found out how old I was—saying something like, “What? I thought you were nine!” or “No way! My baby sister is bigger than you!”

But Kit didn’t say any of that. Her grin widened, and her eyebrow lowered. “Cool. Me, too.”

Kit’s house was about as opposite of my own plain red brick home as it could get. The house stood at least three stories, and I counted just as many chimneys poking up from the dark green roof. Tons of narrow windows with swirling thin wood trim at the top, like icing on a cupcake, marched up the sides of the white structure. At least, it had been white once. Now it was mostly gray, with long strips of peeling paint curling on the sides. The ceilings of the three balconies that popped out of the sides of the Victorian mansion were painted green to match the roof. It looked like a regular boxy house that someone had added on to, with rooms and porches jutting out in angles. The twisting spokes of the balcony rails were painted in pink and blue, making me think of the ginger

bread house Hansel and Gretel had stumbled upon in the woods. Once, I could tell, it had looked amazing. It still did, but in a faded sort of way. “You live here?” I asked.

“Yeah,” said Kit, shielding her face from the sun with her hand as we looked up at a turret with windows all around that jutted out from the top. Kit pointed to it. “That’s my room.”

“Isn’t it too bright?” I asked.

“I like the sun.”

“Of course,” I said without thinking.

“What do you mean?” Kit lowered her eyes to meet mine, and my face flamed again.

I shrugged instead of answering. How was I supposed to say Of course you like the sun, you are a sun without feeling like a dork? But when Kit’s mouth twitched into a smile I somehow knew she had read my mind.

“So how come I haven’t seen you at school?” I asked.

“Because I’ve never been to school.”

“Ever?”

“Well, not since kindergarten, anyway. It just didn’t work out. You know, teachers telling me what to do, how to behave, how to share and take turns.” Kit rolled her eyes. I laughed.

“Yeah,” I said, “the whole standing-in-line thing about did me in, too.”

Kit raised her fist. “I had to take a stand! Mom homeschools me.”

I shuddered. For a while, back when I was in fourth grade, my mom had to homeschool me after I was in the hospital for a long time. We both hated it. Her voice would go all hard and fake-happy when I didn’t understand something or when she did a math problem in a confusing way. “That stinks.”

“Not really.” Kit shrugged. “I can study whatever I want. Or nothing at all.”

My head jerked back at the thought. Every day that Mom homeschooled me, she had a plan and so many lists. Thinking about Mom made me wonder how long I had been gone. I went up on my tiptoes, trying to figure out which direction led to my house.

Kit’s house’s dirt driveway led to a wooded road, and woods surrounded the house in all directions. I couldn’t figure out which way led to the main drag back toward my house. “Do you mind if I use your phone? I left my cell at home, and my brother’s going to go nuts if he doesn’t hear from me soon.”

The Newspaper Club

The Newspaper Club The Humiliations of Pipi McGee

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Camp Dork

Camp Dork Pack of Dorks

Pack of Dorks Bringing Me Back

Bringing Me Back The Reckless Club

The Reckless Club A Blind Guide to Stinkville

A Blind Guide to Stinkville A Blind Guide to Normal

A Blind Guide to Normal Caleb and Kit

Caleb and Kit