- Home

- Beth Vrabel

A Blind Guide to Stinkville Page 5

A Blind Guide to Stinkville Read online

Page 5

“Morn’n’.” The old man nodded toward Dad and me. There was something funny about his grin, which the girl also seemed to notice when she sat down.

“Gramps!” she snapped. “Why didn’t you put your teeth in this morning?”

The old man chuckled like not wearing your teeth to a restaurant was the best joke ever. Then he pulled them out of his pocket. He turned and blew on his dentures and I sneezed as a little cloud trickled to my nose.

“I’m so sorry!” the girl exclaimed.

“Ah, just a little sawdust,” the old man said. “Never hurt anybody.” He dipped his dentures in the cup of water, shook them a little, and slipped them in his mouth.

I giggled and he smiled at me, popping the teeth out and back in to make me laugh harder. Then he reached in his other pocket, blew off sawdust in the other direction, and handed me a little piece of wood covered in smooth ridges. I held it close to my face to check it out and slowly breathed, “Whoa!” I got my magnifier out of my back pocket to check out the details. The little piece of wood, only the size of my thumb, was so intricately carved into a little man with a peaked hat and beard that I had no choice but to smile back at its grin. In its hand, it held a dandelion, with half the wishes blown away. I felt little bumps across the gnome’s chest, which I think were little seeds scattered as if they were caught by the breeze.

“It’s a gnome,” the old man said. His cheeks were a little pink.

“It’s amazing,” I said. “Did you carve it?”

“All he does is carve,” the girl muttered.

Reluctantly, I handed it back to the man.

“Nah.” He patted my outstretched hand with his calloused fingers. “You keep him. Gnomes are good luck.”

Funny how that little gift made my eyes get watery again. “Thank you,” I whispered.

Dad and I finished our breakfast slowly, him watching the people around us and me listening to him whisper descriptions.

“It’s not so bad here, is it?” Dad said as the silence between us stretched thin as taffy.

“It’s so different,” I answered, running my thumb along my gnome’s wished-away seeds.

“But the people . . .” Dad tilted his head toward the counter where Gretel was laughing in Grandma’s voice. She swung by, putting a milkshake in front of the old man and telling him she added some extra love.

“When you gonna marry me, Gretel?” the old man asked.

“Ha! You know me, married to this diner for the past forty years,” she laughed.

Next to us, the teenage girl was gently scolding her grandpa again, this time for drinking his milkshake too quickly. Mayor Hank was shaking hands with a mill worker. The door’s bell rang again, bringing with it the sour smell of the Mill and a half-dozen greetings for the newcomer.

I closed my eyes and thought of Mrs. Morris, Kerica, and even Sandi. “The people aren’t so bad,” I finally said.

“I know it’s been tough. I get it. We moved you and your brother, everything is different, and we’re making decisions for you that you might not want or like,” Dad said, his hand curled around his empty milkshake cup. “But this is where we’re at. I need someone—you—to be on my side. Like it or not, this is where we are.” Dad nudged me with his elbow. “But it’d be pretty awesome if you liked it.”

I smiled, squeezing the gnome in my hand. “I’ll try. But Mom and James—”

“I know,” Dad said, “they haven’t seen the good yet.” Dad squeezed his eyes shut and rubbed at them with his thumb and forefinger. “Don’t take this the wrong way, Alice, but it’s kind of funny to me that you’re the one who has started to see the good. You know . . .”

“Because I’m blind?”

Dad smiled, but it was a sad sort of smile. “It’s funny to hear you say it like that. Like it’s a fact. We’ve spent so much time trying to make you having albinism and being blind not, I don’t know, a factor. Your mom worked so hard to make it not a big deal, not even really a thing. Then we move and suddenly, it’s so—”

“Something to deal with,” I finished for him. “I know. But I’m not any different than I was in Seattle. I can still do stuff. I’m still me.”

“Yeah, but your mom, she’s not doing well with the move. She’s not there advocating for you. Not because she doesn’t care or she doesn’t worry. Believe me, she does. But she’s struggling.” Dad ran his thumb down the side of the cup, the scratching sound breaking the air around us. “You don’t know this, but she’s been like this before. After James was born, it took a few months. When she realized she could take him with her and still work, it seemed to help. After you were born, she was so blue it took both of us four months to notice that your eyes worked differently.”

Dad hung his head lower. “I shouldn’t be dumping this on you.”

“No.” I slipped my hand over his like I was the grown-up. “I want to know.”

“I thought it’d make her worse, you know. Finding out you were blind. But it almost kick-started her feeling better. Suddenly she had a mission—to be your advocate. But I’m not sure if she’s up to it right now.”

“Then I’ll do my own advocating,” I said with more confidence than I felt.

“It might not be that simple.” Dad squeezed my leg. “But I’m proud of you. I’m proud of you for trying.”

“I’m not going to that school, though.”

Dad shrugged. “Nothing is decided. We’re just exploring all the options. We’re going to do what’s best for you, even if you don’t realize it.”

“I’m not going.”

“We’ll see.”

Stomach stuffed, I sadly left half my pancakes at the table when Dad said it was time to go. I thanked the old whittler man again as we headed out. Mayor Hank was using thumbtacks to post a flyer by the door. He handed us an extra copy. It was about the Sinkville Success Stories contest.

“Where now?” I asked Dad as we got in the car.

“Home,” Dad answered, and it sounded like a heavy word, one that fell between us like a brick. Because, for a few moments in the diner, it did feel like our home was here. Now if only I could get James and Mom to see that. “Home for you, work for me.”

“Can we go to Target or Walmart first?” I asked.

“Do you need something?” Dad asked.

“Plates,” I answered. “Plates and real forks.”

Dad laughed. “Yeah, we can make a pit stop for those.”

Chapter Five

Wrestling piglets isn’t a usual gig for a journalist, even a journalist whose usual gig is traveling the world. But when Mom was sent to Montana, she wasn’t given any instruction other than to find a “slice of life story.” That’s journalism code for “we have pages to fill.” After spending the day hiking and not seeing anything particularly page-worthy, Mom ended up at a rodeo. She made the mistake of telling one of the cowboys that she was a Geographic World magazine journalist.

Soon a twangy voice called over the loudspeaker: “We have a real-live reporter visiting us from Geographic World magazine! Would Dana Confrey come down to the rodeo floor?” Not knowing what else to do, Mom made her way down to the dirt ring. The loudspeaker continued, “Miz Confrey’s looking for a rodeo story, so we’re gonna give her one to remember. She’s gonna kick off tonight’s rodeo with some pig wrangling.”

Before she could say no, Mom was pushed out into the rodeo dirt. From a far corner the gate opened. Out came a squealing greased piglet.

“What did you do?” I had asked Mom when she told me this as a bedtime story years ago.

“What could I do? I wrestled that greasy pig to the ground.”

I stood just outside Mom’s bedroom door the next morning, wanting to tell her I’d try harder, that I was sorry. But Mom didn’t come out. James brushed against my shoulder in the hall.

“Where are you going?” I asked, noticing he already had a backpack on his shoulder.

“The lake.”

“It goes by the library,�

� I pointed out.

“I’m leaving now.”

I rushed to change out of my pajamas. The only thing I had clean was a pair of too tight jean shorts and a T-shirt. Maybe part of this advocating for myself could be getting Mom to teach me how to do laundry.

Even though I was desperate to leave when James did, I ran back to my room for my cane. I held it in one hand and latched the leash to Tooter’s harness with the other. James might not walk me to the library, but I’d follow him until we passed the library. I whispered, “Advocate for yourself.”

If James was surprised to see me with my white cane, he covered it up well. I don’t use it much, since I always have someone to take me wherever I want to go. But I figured I better start, especially if I was going to convince Mom and Dad I didn’t need to go to a stupid special school.

The cane has a metal tip so I can feel changes in the sidewalk. James kept pace about two or three sidewalk squares ahead of me, but he didn’t cross any streets until I was beside him. Not that he’d look at me or anything.

I can make out street corners and driveways, but the cane keeps me from tripping over cracks in the sidewalk or stuff people leave out, like toys or yard equipment. Our house is always super neat so that I don’t trip over stuff, so it amazes me how other people don’t put things away.

I kept count of how many blocks we walked (easy enough to do since Tooter stopped to pee at each intersection) and I paid attention to the curves on the path. Tomorrow, I thought, I will do this myself.

“What are you doing?” I asked James as we passed the library. He didn’t pause or look up. His hands were jammed into his pockets and his hair was hanging in his face. I wondered how he could see. Maybe he needed a cane, too. Or a haircut.

“Going to the lake,” he answered, annoyed.

“I know,” I snapped. “But what are you doing there?”

“Don’t worry about it,” he sighed and raked his hands through his hair, glaring up at the sky. “I’m heading home at three o’clock. I can’t stop you from following me.” I almost told him I could make it fine with my cane and Tooter. But I didn’t.

Inside the library, Kerica wasn’t sitting in one of the hand chairs like usual. Mrs. Morris was there, though, watering the plants on the windowsill just behind the chairs. “Kerica’s over by the computers,” Mrs. Morris said, gesturing with her thumb toward the back of the room. I could hear the steady clicking of Kerica’s fingers typing. Mrs. Morris’s eyes lingered on the cane for a second.

I felt suddenly stupid holding it, like I was posing as a blind person, holding a cane and a dog’s leash. I had to remind myself that I was actually blind, so it kind of made sense. Part of me wanted to fold the cane back up and shove it in my backpack, though. I let go of Tooter’s leash, and he jumped up onto one of the chairs, making it after the fourth attempt. It’s funny; he used to be able to make it in just one leap. Now each day it seemed to take more work to get into the same chair.

I decided to use the cane, arching it back and forth over the carpet toward the sound of the clicking. It saved my hip from banging into the edge of a bookshelf.

“Hey,” Kerica said as I approached. She glanced quickly at the cane and then back to her screen.

“Hey.” I pulled back the chair next to hers and sat down. “What are you doing?”

“Nothing, really.” Kerica minimized the document she had been working on.

“Huh,” I said. “Sounded like you were typing pretty fast for nothing.”

“Oh. It’s just . . .” I saw the flyer for the Sinkville Success Stories contest on the desk next to the monitor.

“Are you entering the contest?” I bounced a little in my seat. “What’s your idea? Maybe we can compare notes!”

Kerica bit her lip. “Are you serious? You’re really going to enter it?”

I stopped bouncing. “Yeah. Why wouldn’t I?”

“Well. You just moved here and . . .”

“And what? I may have just moved here, but I can see things with a fresh perspective.”

Kerica’s eyes widened.

“Oh, come on!” I snapped. “It’s an expression.”

She sort of shrugged and turned back to the monitor. “If you want to work together, just ask.”

“Huh?” She was totally losing me.

“I get that you want to enter. Everyone does,” Kerica said. Her voice was suddenly the cold, crisp voice she used with Sandi. “But I’m not going to do it for you. Sandi already tried that earlier today and I told her no, too.”

I folded my cane back together with quick snaps. “What are you talking about?”

“Look,” Kerica turned to face me, but she didn’t meet my eyes. “I’ve gotten burned before being partners with people on projects and doing all the work myself. I’d rather work alone.”

I felt my face flame. “You don’t think I can do it alone?”

“I think you’re going to need a lot of help. And I’m not . . . I don’t—”

“I get it,” I snapped. “You work alone. Guess what? Me, too.”

Kerica stared at me. “You’re seriously going to try to do this on your own? You don’t even know the town. You just moved here! All you know about Sinkville is your home and the library. That can’t be a success story.”

It was on the tip of my tongue to say that I also had been to the Williams Diner. “Why are you being such a jerk?” I said instead.

“Why won’t you admit that you’re totally going to need me to do all of the work for you?” Kerica’s voice lowered into a hiss. “My mom already lectured me about it the whole drive here. First, I have to be nice to Sandi even though she’s never nice to anyone, just because she’s one of Mom’s students. Now, I’ve got to help you with this project, just because you’re . . .”

“I’m what?” Now my voice was just as cold as Kerica’s.

She sighed and rolled her eyes. “Because you’re blind and sad.”

I whipped my folded cane into a straight line with way more force than necessary and slammed my sunhat back on my head. “I never asked you to do anything for me. And just for the record, I wouldn’t want to work with you on the project. You’re too bossy and too much of a snob!”

Mrs. Morris stepped toward me as I rushed from the children’s section, dragging Tooter by his leash. Tooter’s back legs went limp so I scooped him up under my arm and kept walking.

Mrs. Morris had a bunch of books in her hand and a kid trailing her. He was asking for everything on local history and successful businesses. Another essay writer. But Mrs. Morris wasn’t listening to the kid. “Kerica?” I heard her half-question, half-yell.

I paused by Mrs. Dexter at the front desk. Trying not to breathe in her perfume of rotting lavender, I asked how to get to the lake. Still talking like I was deaf instead of blind—extra loud and slowly—she gave me directions.

“Wait! Shouldn’t I tell your dog?” she called as I stormed out of the library.

Maybe Part One of Sinkville Success Stories would be on the shores of the lake. Or at least maybe I’d find out what James had been up to lately.

“Hey!” a shaky voice called just as I got my cell phone out to call James. I was so startled, I dropped the phone. Using the cane, I found it without having to go on my hands and knees. I bent, picked it up, and turned toward the voice. I squinted through my darkened lenses.

Luckily, it wasn’t too bright today, but I guess I was more nervous than I thought about venturing out solo because everything was pretty scattered. I had followed Mrs. Dexter’s directions to take the sidewalk from the library, to cross the street, and to turn onto a dirt pathway cutting though a wooded area to the lake. I saw the bluish-gray water stretched out to my left and breathed in the algae and fishy smell. The lake was a lot bigger than I had thought it would be.

I couldn’t see the shore well. I could go down to the shoreline and maybe have a better chance of finding James. (Think how impressed he’d be that I got here alone!) But I’d als

o have a much better chance of getting hopelessly lost if I went off the path. The cane would keep me from tripping. But would it keep me from totally losing any sense of direction? Not so much. So I was about to do the unforgivable—call James (think about how annoyed he’d be that he had to rescue me!)—when I heard the voice.

“James?” I called back, even though the shaky voice didn’t sound anything like my brother’s.

“Nah,” the voice, closer now, replied. Then I saw a man curled around a wooden cane like a comma, taking small, tired steps in my direction. A couple strides and he was beside me. Just like I had thought, it was the old whittler man from the Williams Diner.

“Well, now,” he said, leaning heavily on his cane. “It’s my gnome girl.”

“Hi!” I said, feeling my face split into a grin. I pulled the gnome out of my pocket and showed it to him. “This is lucky!”

The lake wasn’t supposed to be there.

Mr. Hamlin, the old whittler, told me so in a voice softer than the water that lapped against my feet. We sat on a dock that stretched out over the lake, Tooter curled against me snoring. Mr. Hamlin sat in a folding chair with peeling plastic weaving. A small blade in his right hand ate at a lump of wood cupped in his left. The curling strips that fell around him reminded me of getting my hair cut.

Mr. Hamlin said the lake used to be farmland. “If you were to walk over that way,” he said, not looking up from the wood but throwing out his curled hand toward the left, “you’d see what looks like a road going straight into the water. That’s my old driveway.”

M. H. Bartel Paper Company apparently needed a body of water to draw from during operations. They purchased about a half-dozen farms, the Hamlin property included. All in all, the lake totaled a couple hundred acres. “Town needed jobs,” Mr. Hamlin said. “I had just gotten the farm from my papa. That Bartel money was more than I’d make in a decade of farming. Didn’t think too much ’bout it. Signed the paper.”

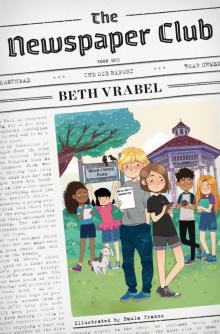

The Newspaper Club

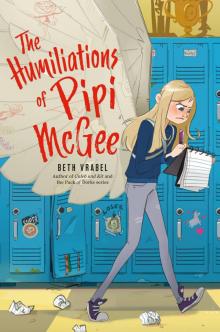

The Newspaper Club The Humiliations of Pipi McGee

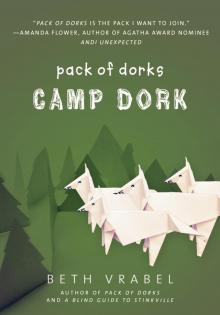

The Humiliations of Pipi McGee Camp Dork

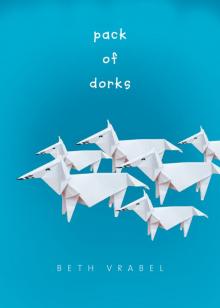

Camp Dork Pack of Dorks

Pack of Dorks Bringing Me Back

Bringing Me Back The Reckless Club

The Reckless Club A Blind Guide to Stinkville

A Blind Guide to Stinkville A Blind Guide to Normal

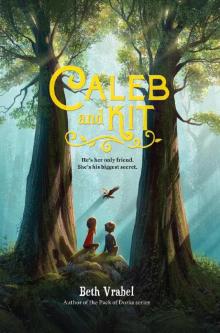

A Blind Guide to Normal Caleb and Kit

Caleb and Kit